Starting up a new business is crazy. If you’ve ever been a part of one, you know just how crazy it can get. Chaos all the time, late nights, weekends, little sleep, and lots of stress. Having done it a few times, I think this is largely because everything we do is “open ended” – it’s one difficult problem with no clear answer after another. It’s exciting… and exhausting.

After a few years, it usually settles down to a rhythm of craziness. You know what your product is, what your goals are, where the pain points are… there’s a semblance of a plan, and while you’re not relaxed yet, it’s not as bad as it was in the first few years (or maybe you’re just used to it now?).

Typically around this stage you start employing people at a lower level – assistants, receptionists, production staff, sales associates, apprentices or trainees. These people will end up doing a lot of the day-to-day work in the business, and certainly most of the menial work.

The tasks they do tend to be things that are similar each time, with minor variants. For example, receiving a delivery (different contents, size and number of boxes, but everything else is similar), picking and shipping a mail order (every order has a different combination of items, but there’s more in common in the process than not), sending a newsletter (different images and text, but similar layout, proofing and sending process), ordering stock (same suppliers, but different amounts).

Typically these people are cheaper to employ, but take up most of a manager’s time – finding them, training them, making sure they do not make too many mistakes (but also, fixing those mistakes).

All employees need guidance, but lower level employees tend to need more help than senior employees – they’re less experienced, and less able to make the right decision when faced with complex options (partly due to their inexperience, but mainly their lack of understanding of the ultimate business goals and externalities). That’s not bad, it’s just a natural aspect of how a business grows and learns.

If you as the business owner kept on doing these low-level things yourself, you’d do a good job at it – you’re sensitive to how customers react when spoken to a certain way, for example, and you know the damage that can be done if you do something that causes a customer to be unhappy. In short, you’re skilled at thinking how a customer thinks. As you see new opportunities for improvement – reducing costs, increasing customer satisfaction, reducing risk, making more sales, removing opportunities for errors, improving quality – you make those changes “on the fly”. In fact, you pretty much just do them “naturally”.

But you can’t keep doing that stuff! You need to meet with big clients, address product issues, steer the ship, plot the course, find new senior staff, develop the next product – high level stuff that paves the way for the next five years of glory.

So how will your employees do the right thing? As I see it, there’s two main approaches:

The “brute-force” approach

You employ battle-hardened managers. They know your type of business well, they have experience in similar-sized businesses, they tend to work long hours. They check closely on what each employee does, disciplines them to improve, metes out positive feedback, and often just picks up the work themselves when an employee drops the ball. Because they take the pain away from you, and get things done, they’re deservedly well paid.

You probably know some people like this – you might even employ some people to do this! These managers are indispensable to the business (in a bad way – if they leave, you’re in big trouble). They spend most of their day anticipating and fixing mistakes.

I consider this “brute-forcing” the problem. You bring to bear a strong tool, a big lever, and get shit done by sheer force of will. It’s sustainable in some ways, but it’s stressful for the manager and tends not to build a culture of employees who feel loyal to your company (maybe meaning higher employee turnover, or worse). It can mean there’s little room for advancement for existing employees, and that you’ll always need that brute-forcing manager operating at peak capacity for the business to function – forever.

The business-process approach

You make checklists – the “manifestation” of business processes – to help employees do things the right way. You create a culture of using checklists for repeating business processes – it becomes a hard rule that no one starts work on a repeating business process without using a checklist.

You promote promising employee-level people who do well following and improving checklists to be “coordinators” – a salary and responsibility-level increase, but not to the level of a manager. Their job is to keep the trains running on time, to ensure every employee is using checklists, and to improve those checklists (for example, to cover more edge cases).

Employees are clear on what’s expected from them, coordinators can easily see that work has been done right, and everyone’s stress level is reduced as productivity increases.

You become immune to employees leaving – sure, finding new employees is always a hassle, but once appointed they complete training and start using checklists to do their job, and they’re “low maintenance” soon after. Of course, they still need to be mentored and developed, but the low level day-to-day stuff takes care of itself when there are clear business processes implemented in checklists.

Consider some big, established businesses you come in contact with day-to-day, for example, Walmart or McDonalds. You’re not that size yet, but you want to head in that direction. Perhaps you’ll never make billions of dollars, but there are some learning opportunities there.

Those businesses are highly process-driven, in fact, that’s one of the main things that define them. Skilled, talented and experienced people have established on the best way to complete tasks to get the output quality to meet the standards (safety, customer happiness, marketing, accounting, whatever), and using available resources in an economical way. They have tested the processes, considered most outliers, timed tasks, and allowed for things to go wrong.

So now those businesses can employ less-skilled, nascent-talent, inexperienced – cheaper – people to do most of the day to day work.

Let’s collect the mail 📬

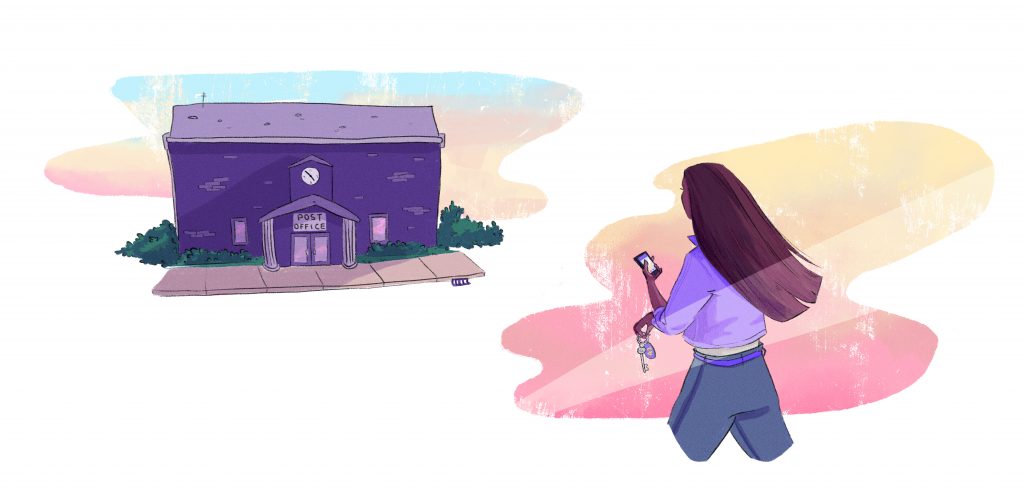

Consider a task common in every small businesses – dealing with incoming postal mail. If you have more than 10 employees, you probably have to deal with a non-trivial amount of incoming business mail each week. Sure, a lot of stuff is done by email these days, but there’s still letters from the tax office, bank, insurance, local and state governments that are important (or rather, any one item might be important).

On the surface, it’s pretty basic – collect the damn mail, throw it on the desk of the bookkeeper and have done with it…

But maybe that’s not always the case. What if you have PO Box as well as a mailbox on the street? What if the person who normally collects mail is on vacation for three weeks? What if the bookkeeper is away for a month, and there’s urgent mail to be processed? What if you get sent a private letter and the bookkeeper opens it? If any of these have happened to you, you know where I’m coming from. If they haven’t, you’re lucky – those ‘penalty interest’ letters from the tax office are no fun!

Collecting mail is something that happens every week day, forever. If it being done wrong has ever caused annoyance, it’s a good candidate to fix once, properly and permanently. A checklist is ideal for this! It’s always the receptionist who has this duty in my businesses. Maybe the checklist would be something like this:

▢ Collect mail

▢ Discard junk mail

▢ Open envelopes

▢ Scan pages

▢ Email scanned items to the right people

For a checklist that short you gotta wonder, is it even worth it? Well, I’ve simplified it for this example, but let’s go with it for now. Murphy the Optimist said “Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong”. Having run several small businesses for 18 years now, I can 100% confirm that’s true, as I will now illustrate. Ready?

“Collect mail” seems simple enough, but two of the main reasons for having a checklist is scalability and cross training. If the Receptionist is away, the Office Assistant should be able to take care of the mail collection in their stead… but collect the mail from where?

War story # 1: Some years ago our Receptionist on leave for a week, and the Office Assistant took on her duties. But the Office Assistant did not know we even had a PO Box, so they only checked the kerb-side mailbox each morning. It took a week for the accounting department to wonder why we were not getting any payment cheques from our customers!

War story # 2: More recently, the Receptionist was away again. This time, a young technician trainee from the back office was tasked with mail collection. Smart guy, but never done something like this before. No problem, our “Collecting the mail” checklist (we made it after the last debacle) was comprehensive, right?

He collected the mail from the PO Box, but did not look at the mail he collected. Turns out there was a card for a parcel to be collected at the Post Office counter. Back at our office, he thought the card was just junk mail from the postal service, so discarded it. After 10 days of the parcel not being collected, the Post Office returned it to the sender in a distant country. The sender was doubly annoyed – they had paid for postage, to return some faulty goods! :/

We could “brute-force” this task of course – only send people to collect the mail who understand the risks, someone who has been around the block a few times… someone more senior. Of course, that’s a description of an employee who has more valuable things to do! Or, we could have a manager check in with the employee several times during this process, but that’s even more time-wastey.

Or we could go the other route: the business-process approach. It’s more work up-front, but has a long-term payoff. Define in a lot of detail exactly how mail should be collected and processed. Have a training process to train new people to do it (perhaps just as simple as, do the mail collection and processing task with the experienced Receptionist once or twice, then you’re on your own). Give feedback. Empower employees to succeed – by having all the info up front, they know what’s expected of them.

So let’s make the start of our checklist more comprehensive and granular:

▢ Collect mail keys from slot 42 in key locker behind reception desk

▢ Collect mail from PO Box 112 at Smallville Post Office; 2397 Main St; 9am to 5pm week days

▢ Check for parcel collection cards; collect any parcels from counter at Post Office

▢ Collect mail from our kerbside letterbox (456); re-lock padlock

▢ Return keys to slot 42 in key locker

Being this specific we remove ambiguity and cover some issues we’ve had (and, we “close the loop” on the keys, so they’re always we they’re expected to be!).

Maybe you’re rolling your eyes and thinking All this shit for just collecting the mail?! I say, “Yes – and not just mail, but most other tasks as well!”.

When you’ve done all this work, you largely inoculate yourself from employees leaving your business. You just crank up the recruitment process (a separate business process, similarly detailed, natch), select the new Receptionist employee. The first few days they need extra supervision, but from then on they can operate mostly autonomously, because checklists cover most of their duties.

Extend this idea to other roles in the business, say, Order Taking, Cash Handling, Ordering Supplies, Completing Payroll and we see increasing efficiencies that compound – the best business processes are modular, and connect with each other.

They all mean you as the owner can worry about the big picture stuff, knowing the small stuff is done right by people who feel in-control and responsible for their daily duties – all because of business processes.

In Part 2 (scheduled for release Dec 15, 2018), we look at creating a business process for collecting and processing postal mail in more detail.